The first photos that Brian Epstein commissioned of the new Fab Four were taken on waste ground in north Liverpool.

Little did John know of the significance of the location.

Find out more in this video

The first photos that Brian Epstein commissioned of the new Fab Four were taken on waste ground in north Liverpool.

Little did John know of the significance of the location.

Find out more in this video

Here in Liverpool, we are trying to raise £60,000 to create and erect a statue to the great Brian Epstein. Without Brian, The Beatles would never have made it out of Liverpool. As Beatles fans, let’s make this happen.

We have already raised nearly £5,000, so we need your help. There are lots of benefits and rewards for every pocket. The statue is being made by Andy Edwards (below) who sculpted the amazing Beatles statues at the Pier Head.

Simply go to the fundraising site and decide how much to give. £60,000 between us all isn’t much at all.

Thank you

David Bedford

On 27th August 1967, Brian Epstein was found dead in his London flat. His Personal Assistant, Alistair Taylor, discovered his body. Many people still think that Brian committed suicide. Alistair explained what really happened in an interview with me for Liddypool, as he discussed Brian Epstein’s death, a very personal story.

“Brian had called me on several occasions threatening to commit suicide, and when I went round to his flat, he would be sitting there quite calmly having a drink and wondering what the fuss was about.

“Brian was into drugs and becoming more and more dependent on them. I could see how this changed his character, with him being more depressed. Many have suggested that The Beatles didn’t need him any more. However, Lennon summed it up when he said, ‘Well we’ve f***ing had it now’. Most importantly, the four Beatles were quite clear on this: if Brian couldn’t be their manager then nobody else could”.

“I remember coming home from San Francisco, walking through the door and saying hello to my wife Lesley, when the phone went. Epstein’s secretary rang and said she couldn’t get an answer from Brian. I had to apologise to Lesley and head off there. Naturally, Lesley wasn’t impressed, but I had a feeling something was wrong. We went in to the flat, and I just remember Brian lying there and I immediately knew he was dead.

“Therefore, I looked around, and presumed it wasn’t suicide, because firstly there was no note, but more importantly, I could see his pill bottles next to his bed, half full with the lids on. There were some letters on the bed and his favourite chocolate biscuits on a plate.”

Most importantly, what caused Brian Epstein’s death? The coroner confirmed what Alistair said; it was an “incautious self-overdose”. The amount of drugs in his body was consistent with a build up over the previous weeks, and this would have had the side effect of making the user more and more forgetful. The official cause of death was ‘Carbrital poisoning’. ‘Time, place and circumstances: 3.00 p.m., Sunday 27 August 1967 at 24, Chapel Street, Westminster. Found dead in bed. Coroner’s conclusion: Incautious self-over-dosage. Accidental death’.

Brian Epstein’s body was brought back to Liverpool, and his funeral was held in his local synagogue at Greenbank Drive in Wavertree; he was buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Aintree, North Liverpool. His contribution to the group’s success has been diminished over time, but to those in the know, it is immeasurable.

Without Brian Epstein, The Beatles would never have got out of Liverpool, obtained a record deal, and gone on to have the fame and fortune they did. (This is an excerpt from Liddypool: Birthplace of The Beatles)

In 2019, Liverpool is now looking to raise the money to erect a statue to Brian Epstein. More news will follow. See www.epsteinstatue.co.uk

David Bedford

Were The Beatles and the Fab Four different? Much has been made of the drumming skills of Pete Best and Ringo Starr, and opinions are often at odds. Each has been praised for his talent, or criticized for his lack of it.

Pete Best was removed from The Beatles because of George Martin’s comments at the end of their June 1962 audition. Was it a clash of personalities, haircuts and the myriad other reasons given for Pete’s “dismissal”? Or was there something more fundamental going on which may have gone unnoticed? David Harris, Brian Epstein’s lawyer, confirmed that when Pete Best left, The Beatles effectively disbanded and then re-formed with Ringo. Was this more than just a legal sleight of hand that happened in the blink of an eye?

There are certain crisis points in Beatles history where the evolution of the group required a personnel change.

On 6th July 1957, Paul McCartney watched The Quarrymen perform a mixture of country, rock ‘n’ roll and skiffle. Yet rock ‘n’ roll would always remain John’s first love. The Quarrymen lacked the expertise to make that musical leap from a skiffle group to rock ‘n’ roll. John knew that if they were going to become a rock ‘n’ roll group, they needed more skilled musicians. Thankfully, Ivan Vaughan introduced him to his mutual friend Paul McCartney. All John had to decide was whether they would continue playing just for fun, or take themselves more seriously. Should they bring in a musician who had the talent to improve them?

By inviting Paul to join The Quarrymen, John knew that most of his friends would soon be leaving. Rock ‘n’ roll bands didn’t need a banjo, washboard or tea-chest bass. That reality hastened the departures of Rod Davis, Pete Shotton and Len Garry.

What John and Paul realised after Paul botched his solo on “Guitar Boogie” was that they needed a lead guitarist. Thankfully, Paul knew someone who could amply assume the role: George Harrison. Five months after John met Paul, George had replaced Eric Griffiths, and Rod, Pete and Len had departed. Only Colin Hanton, the drummer, remained. The nucleus of The Beatles was in place; John, Paul and George were now together.

John, Paul and George were desperate to have their own rock ‘n’ roll group. They offered a spot in the band to Rod Murray or Stu Sutcliffe, depending on who could get a bass. Stu joined the group when he purchased a bass with the proceeds from the sale of one of his paintings.

As they ditched the Quarrymen name, John, Paul, George and Stu needed a drummer. Their new manager, Allan Williams, recruited Tommy Moore, and, at long last, they were a rock ‘n’ roll group. Through Tommy first, then Norman Chapman, the boys were able to convince Williams to get them bookings. Later, with new drummer Pete Best on board, to send them to Hamburg.

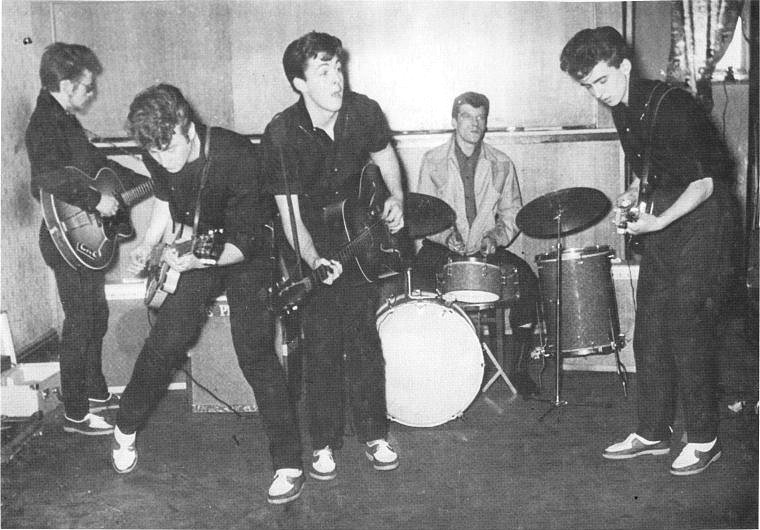

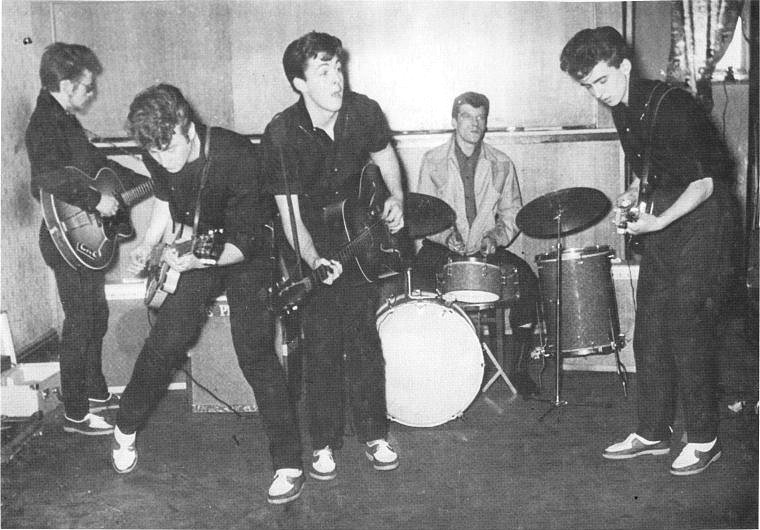

With Pete now in the group, The Beatles became the greatest rock ‘n’ roll group Liverpool or Hamburg had seen. As Beatles promoter Sam Leach observed; “When The Beatles came back from Hamburg, they were the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band anyone had seen. Only those of us on the scene then saw The Beatles at their best: they were pure rock. They lost some of that when Brian put them in suits, but it worked, and you can’t argue with it.”

As John Lennon said: “We were four guys. I met Paul and said, do you want to join my band, and then George joined and Ringo joined. We were just a band who made it very, very big; that’s all. Our best work was never recorded. In Liverpool, Hamburg and around the dance halls, and what we generated was fantastic when we played straight rock. There was nobody to touch us in Britain, but as soon as we made it, the edges were knocked off. Brian put us in suits and all that, and we were very successful, but we sold out. Our music was dead before we even went on the theatre tour of Britain.” (Rolling Stone Interview).

The Beatles did their best work in Liverpool and Hamburg. John is acknowledging that the group was at its best with Pete on drums. This is a point easily confirmed by any fan who saw the band perform in Liverpool or Hamburg. There was no one to touch them. However, John’s comments need to be taken in context. He loved those early days playing rock ‘n’ roll, but his words shouldn’t be viewed as a criticism of Ringo.

This transitional period also saw a crucial change on bass guitar. Although Stu Sutcliffe was a decent rock ‘n’ roll bassist, they needed Paul McCartney. With Paul on bass, they could take it up a notch.

What we witnessed during the summer of 1962 was the end of The Beatles. They were the great rock ‘n’ roll group that had conquered Liverpool and Hamburg. Through Pete Best’s driving beat, Paul’s thumping bass, John’s fiery rhythm and George’s infectious rock ‘n’ roll guitar licks. What we then witnessed, with the introduction of Ringo, was the birth of the Fab Four. This new pop group would conquer the world. In 1962, they rocked in the year, but ‘popped’ it out in the charts with their new brand of music. They were at last achieving Brian Epstein’s vision of a polished, theatrically-astute and aesthetic pop group.

When Brian first saw them on at the Cavern, they were scruffy rebels in black leather. They were rocking the joint while eating, drinking, smoking and clowning around. When they were presented to the music press in 1962, they were four polite, cheeky, suited Liverpool lads. Brian’s vision of musical theatre was coming to fruition. His “boys” were now presentable in stage costumes with a rehearsed script and a set list. They even bowed at the end of their performances, much like a curtain call for a play. Their shows became carefully-crafted pieces of musical theatre. This was a huge leap into the unknown for the band, but one fully-orchestrated by Brian. The Beatles had evolved into the Fab Four. We couldn’t have both; one of them had to go, and the old style Beatles took the fall.

Things didn’t quite work with Pete, even though he was perfect for The Beatles were doing at the time. The Beatles were playing covers of other artists’ songs. There were certainly no documented issues raised prior to George Martin’s comments at EMI in June 1962. Ringo wasn’t even the first choice to replace Pete. What would The Beatles have been like had they hired Bobby Graham, Ritchie Galvin, Johnny Hutchinson ?

Whatever magic potion he possessed, Ringo fit in perfectly with John, Paul and George, and it worked; history confirms that. As with any team, The Beatles proved that the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. All that mattered was how they worked together. The group would always be greater than the individuals, regardless of talent. None of the Beatles was considered to be the best at his chosen instrument in Liverpool. Together they were greater than any musical team had even been, and likely will ever be.

“Pete Best was good, but a bit limited,” said Paul. “You can hear the difference on the Anthology tapes. When Ringo joins us, we get a bit more kick, a few more imaginative breaks, and the band settles. So the new combination was perfect: Ringo with his very solid beat, laconic wit and Buster Keaton-like charm; John with his sharp wit and his rock ‘n’ rolliness, but also his other, quite soft side; George, with his great instrumental ability and who could sing some good rock ‘n’ roll. And then I could do a bit of singing and playing some rock ‘n’ roll and some softer numbers.” (Anthology).

In “Finding the Fourth Beatle“, we have analysed Pete’s drumming on the Tony Sheridan recordings from June 1961. On the accompanying CD, you can also hear the Decca audition from January 1962. Pete was a more-than-capable player. Extensive research conducted with various Merseybeat drummers about Pete’s drumming resulted in high praise from so many of them.

Billy Kinsley played in the Pete Best Band. He is adamant that they didn’t get rid of Pete because he was a poor drummer. “You ask drummers who were around at the time,” said Billy, “and they say that Pete was a great drummer. I never had a problem at all with Pete. He was great, absolutely superb. Nothing against Ringo, but there was nothing wrong with Pete. However, John, Paul and George knew nothing about the recording business, and nor did Brian. If you saw any of those gigs at the Cavern , all the girls were screaming for Pete. That’s what The Beatles was all about; those three crazy guys and the moody guy who didn’t smile or was quiet, but it worked. Getting rid of him didn’t make sense to us.

So if fellow musicians didn’t see a problem with Pete, what was it? Was there a power shift within The Beatles from John to Paul. Paul’s repertoire and more eclectic song choices would appeal to a wider variety of audiences. Theywere better suited to a group who wanted to make, and sell, records. When it came to covering some of the greatest rock ‘n’ roll and R&B songs, The Beatles with Pete were second to none. John admitted that.

However, for a group writing its own commercial pop songs, a change of direction was needed, and that meant a drummer who was used to playing a more varied song selection. They found that drummer in Ringo Starr, who had performed with Rory Storm and The Hurricanes at the Butlin’s holiday camps, entertaining audiences other than those at the Cavern and the clubs of Liverpool. Brian Epstein was desperately trying to get The Beatles away from those clubs, and John, Paul and George knew that.

So, when Ringo joined the group, they went from being The Beatles, the rock ‘n’ roll kings, to the Fab Four, the greatest-ever pop group. It is possible that, by changing drummers, John was trying to suggest that The Beatles were dead; long live the Fab Four. Both were great bands in their own right, and each had a great drummer in his own right. Pete Best helped The Beatles conquer Liverpool and Hamburg, and also secure Brian Epstein, the manager who would make them famous and attain the record deal they craved. For his contributions, Pete Best should be celebrated and thanked.

Read the full story in Finding the Fourth Beatle.

It is ok to celebrate and like both Pete Best and Ringo Starr; The Beatles were dead: Long Live the Fab Four.

David Bedford

August 1962 was a turbulent month for The Beatles. In trying to find a replacement for Pete Best, Brian had approached Bobby Graham, Ritchie Galvin and Johnny Hutchinson. Ringo, the drummer from Rory Storm and the Hurricanes with whom they had played before, agreed to join The Beatles. His debut was at Hulme Hall in the Victorian Model Village of Port Sunlight, Wirral, on 18th August 1962. The Fab Four was born.

In an interview for The Fab one hundred and Four, Ian Hackett had suggested The Beatles for a previous dance. His father, Harry, booked the group for that legendary debut appearance of the first Fab Four line-up in August 1962. “Our home overlooked the Dell, a particularly lovely landscaped part of the village,” recalled Ian. “It was just a few yards from Hulme Hall, the Bridge Inn and the Men’s Club. While selling the Liverpool Echo outside Lever’s, Monty Lister, one of my customers, approached me. He was the editor of the Port Sunlight News, with an offer I couldn’t refuse.

“Back in the spring of 1962, Harry, as Captain of the Golf Club, organised the Club’s annual dance. He chose Hulme Hall as the venue, July 7th as the date and The Modernaires, as the main band. Then he asked me if I could think of a band to fill in during the Modernaires’ break. I suggested The Beatles.

“On 7 July 1962, the Golf Club Dance came,” recalled Hackett, the first of four appearances by The Beatles.

“They went down really well with my friends, although dad got some complaints about The Beatles.” In spite of those complaints, they booked The Beatles to appear again on 18th August 1962. Little did they know how significant this day would be.

“By having The Beatles headliners at Hulme Hall on August 18th, this showed that not all the adults were hostile. But there was a mass female chanting of ‘We want Pete!’ when they introduced their new drummer.

“The make-up of the audience was different for this show,” recalled Ian, “as there were more young people than locals. The problem was that the local people were angry as the young interlopers wanted to show support for Pete Best. The Beatles never stood a chance. I was glad for this one that my dad took the flak, and not me!”

In spite of the audience reaction, Ian was impressed with The Beatles that night. “I loved their treatments of ‘Twist and Shout’ and ‘Besame Mucho’” he said. “John’s harmonica in general was great, but especially on Bruce Chanel’s ‘Hey Baby’. At that stage, they weren’t playing that many original songs.”

No photos are known to exist of The Beatles at Hulme Hall. However, I discovered a photo of Gerry and the Pacemakers performing there later in 1962.

Ringo, because of the animosity in the crowd, was not enjoying the night of his debut. “I ran into a miserable-looking Ringo in the gent’s toilet during the break,” recalled Ian. “I tried to cheer him up with a smile and an optimistic comment: ‘Don’t worry about tonight. Things can only get better.’ And it was not long before they did.” (David Bedford interview in The Fab one hundred and Four)

You can still visit the hall, though the stage is no longer there.

Discover more about Ringo joining The Beatles in Finding the Fourth Beatle, available in hardback, softback and ebook.

David Bedford

When John, Paul and George decided that they needed to replace Pete Best, following the Parlophone audition, they asked Brian Epstein to find a replacement. The first drummer approached was Bobby Graham, who turned Brian down. Brian Epstein then spoke to Ritchie Galvin, who also said no to The Beatles. Johnny Hutchinson became the third drummer to decline the offer.

The Beatles introduced Brian to Ringo Starr at the Blue Angel Club. Epstein then offered Ringo the opportunity to replace Pete. Brian said that he would confirm the appointment on 14th August 1962. However, Brian then offered Johnny “Hutch” Hutchinson the job of Beatles drummer the day that Brian got rid of original Beatles drummer Pete Best. (see Why Pete Best was not sacked)

On the afternoon of 16th August 1962, Brian told Pete Best the bad news that the other Beatles wanted him out. Pete initially agreed to fulfil the Beatles gigs until Ringo was due to arrive on Saturday. An obvious choice for drummer was Johnny “Hutch” Hutchinson. Hutch had sat in, albeit grudgingly, with The Silver Beatles at the Larry Parnes audition in May 1960. Johnny Hutchinson was the driving force behind The Big Three and the best drummer in the Liverpool. Considering that The Big Three had just signed a management contract with Brian on 1st July 1962, it made sense to approach him to help The Beatles out at short notice.

The Big Three had been playing in Hamburg for most of July before returning to Liverpool in time to appear at the Tower Ballroom on 27th July. Brian asked Hutch to join The Beatles after he returned from Hamburg, and not just for the three upcoming appearances when Pete Best didn’t show up.

I interviewed Johnny for Finding the Fourth Beatle. “I was playing with The Beatles in Chester. With the Big Three playing on the same bill, Brian asked him to sit in with The Beatles. “I had to set up my drums and get dressed for our set with The Big Three, and then go and get changed and go back on stage with The Beatles.” Brian was there and kept looking at me strange. I got off stage after the gig and had to zoom off. Brian said, ‘I was looking at you to see how you’d fit with The Beatles’. I joked, ‘I don’t really.’” Little did he know what Brian was about to say to him.

Johnny Hutchinson was honest; “I don’t remember dates, but I remember exactly where we were,” Hutch recalled. “I was in the Grosvenor Hotel in Chester,” after playing at the Riverpark Ballroom in Chester with The Beatles. “We sat down, and Brian Epstein and Bob Wooler were just looking at me. So I said, ‘What the f##k do you two want?’ And they looked at each other, and Brian said to Bob, ‘What do you think?’ Bob said, ‘Well, Brian, I think John would suit The Beatles down to the ground.’ Then Brian said, ‘I do, too. John, I want you to be The Beatles’ drummer.’

“I told him that ‘I wouldn’t join The Beatles for a big clock. The Beatles couldn’t make as good a sound as the Big Three. My group is ten times better than The Beatles!’ And Brian said, ‘I know, but the Big Three are limited. The Beatles? The world is their oyster.’

“By that, I think he meant that I was the only one in the group who was grafting, really working hard. I was the drummer, doing the singing too, and with only three of us, there was only so much we could do. That’s what I reckon he meant. Brian also said that he had been ‘everywhere to get a drummer and that he couldn’t get one.’ And I said there must be another drummer out there, but Eppy said, ‘there isn’t anyone to suit The Beatles.’ You see, it is often said that I hated The Beatles, but I didn’t. I liked The Beatles, but hated the music. It wasn’t for me, but it suited lots of people. That’s why I wanted to stay with my band.”

Hutch recommended Ringo to Brian. “Yes I did. I told him to go and get Ringo. He’s a bum, he’ll join anyone for a few bob.” Johnny Hutch hasn’t for one minute ever regretted his decision to turn down The Beatles.

Johnny Hutchinson became the third drummer to turn down the opportunity to replace Pete Best in The Beatles. Sadly, Johnny died after a short illness in April 2019. He had become a good friend, and always good company, with some incredible stories. He was never one to make anything up – he always told the truth, which is a rarity.

These revelations from Johnny “Hutch” Hutchinson came from exclusive interviews with David Bedford over a three year period, and feature in his latest book, Finding the Fourth Beatle. You can purchase your copy here.

David Bedford

While Ringo Starr was with Rory Storm and The Hurricanes, EMI granted The Beatles the audition which lead to their contract offer. While the band was heading for the toppermost at EMI on 6th June 1962, Ringo felt he was going nowhere. But then, three offers arrived at once. First, Gerry Marsden asked Ringo to join The Pacemakers, but not as a drummer. “Gerry wanted me to be his bass player!”

“I hadn’t played bass back then or to this day,” said Ringo, “but the idea of being up front was appealing. That you’d never played a particular instrument before wasn’t important back then!” After that, Ted “Kingsize”Taylor offered Ringo the drummer’s job in his group; Kingsize Taylor and The Dominoes.

Ringo’s second offer was from Kingsize Taylor, who promised him £20 per week to drum for his group, The Dominoes. “Ringo was a rare commodity on Merseyside,” said Taylor, “as drummers at this time were very hard to come by. I only asked him to join The Dominoes out of desperation, as Dave Lovelady could not go back to Hamburg .”

Some irony, with this being the reason The Beatles hastily offered Pete the position in August 1960. “Yes,” Taylor continued, “I did, off the top of my head, offer him 20 quid (£20) a week. He accepted it, even though ever liked Hamburg when he was last there.

Along came The Beatles, and the rest is history. Ringo was not a better drummer than Pete; too much of a swing in his rhythm and liked himself more than his music.” (David Bedford interview)

Why did Ringo initially accept Taylor’s offer? Because he had no offer to join The Beatles, and there were no guarantees it would happen. He knew he wanted to leave the Hurricanes, and joining Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes was a step up.

But just when it looked as though his future was clear and that he would join Taylor in September, along came the offer to join The Beatles. But first, The Beatles told Brian to get rid of Pete. Although there had been hints as far back as June, when somebody said to Pete; “they’re thinking of getting rid of you, you know.”

Pete laughed it off, and Brian appeased him. And then, in early August, Pete had his heart set on buying a new Ford Capri car. He mentioned it to Paul, who responded; “If you take my advice, don’t buy it. You’d be better saving your money.”

The Beatles asked one more drummer to replace Pete, on the same day that Pete received the bad news, and the day after Ringo had been offered the job.

Taken from Finding the Fourth Beatle

David Bedford

The Beatles first appeared at The Cavern when they were just The Quarrymen, back in early 1957. It wasn’t until February 1961 that as The Beatles, thanks to Mona Best, made their first appearance at the legendary Cavern Club on Mathew Street. It was a lunchtime session, and it wasn’t long before they made their debut in the evenings too. It was later in 1961 that Brian Epstein walked into The Cavern and saw The Beatles: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Pete Best. Within weeks he had signed them and arranged an audition for them at Decca.

Between their first appearance and their last appearance on 3rd August 1963, they played nearly 300 times. Their final show did not go without incident.

The Beatles were by now nationwide stars, and touring the country after the success of their singles and number one album, “Please Please Me”. The Fab Four were moving away from Liverpool, and setting up home in London, where the national media was located. That last night at The Cavern would be their last, even though they didn’t realise it at the time.

“The crowds outside were going mad. By the time John Lennon had got through the cordon of girls, his mohair jacket had lost a sleeve. I grabbed it to stop a girl getting away with a souvenir. John stitched it back on. They may have altered their style elsewhere, but they didn’t do it at the Cavern. They were the same old Beatles, with John saying, “Okay, tatty-head, we’re going to play a number for you.’ There was never anything elaborate about his introductions.” Paddy Delaney, Cavern Club doorman

Tickets for the final show had gone on sale at 21 July at 1.30pm, and sold out within 30 minutes. The fees for their last Cavern show were £300, a lot more than they received for their first appearance. By then, The Beatles could command almost any fee they wanted. With only 500 people there, at 10 shillings each, it was impossible for The Caverb to make money that night. Brian Epstein promised the club’s compère Bob Wooler that The Beatles would return, but they never did.

“The Beatles were very professional: there was no larking around and they got on with it. We all felt it was their swan song and that we would never have them at the Cavern again. Brian Epstein still owes the Cavern six dates for The Beatles as he kept pulling them out of bookings by saying, ‘You wouldn’t stand in the boys’ way, would you, Bob?” Bob Wooler

The show lasted from 6pm-11.30pm and The Beatles were joined on the bill were The Escorts, The Merseybeats, The Road Runners, Johnny Ringo and the Colts, and Faron’s Flamingos. However, during The Beatles’ set, there was a power cut – which was not unusual at the Cavern – and so they couldn’t use any of their equipment. As the show must go on, Paul McCartney moved over to the piano, and played a song the crowd hadn’t heard before, and wouldn’t hear on record for a few years: ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ from the legendary Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Having shown that The Beatles had outgrown this primitive club, Lennon was not happy:

“We were on just before The Beatles and we were delighted with our reception as everybody was cheering and going mad. The Beatles all had long faces and John Lennon was saying, ‘We never should have come back here.” Tony Crane, The Merseybeats

Although this was the last Cavern appearance, it wasn’t their last Liverpool appearance, which happened in December 1965 at the Empire Theatre.

But for those Cavernites, it was the last time they saw their hometown heroes, The Beatles, in The Cavern.

David Bedford

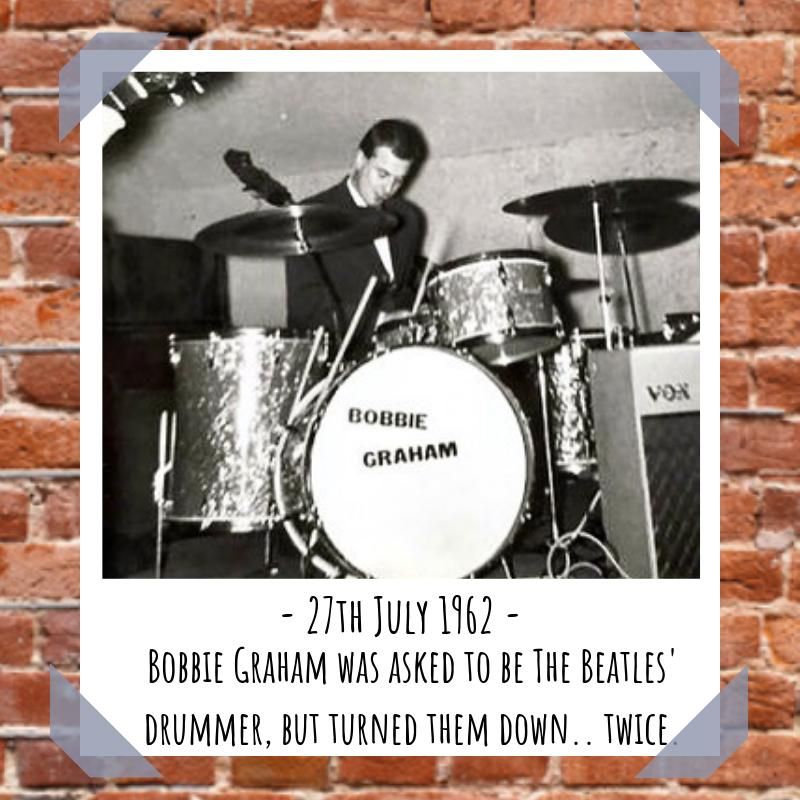

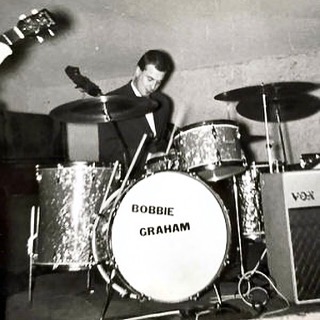

On Friday 27th July 1962, a conversation was about to set in motion a chain of events that would lead to Pete Best leaving The Beatles and eventually being replaced by Ringo Starr.

On Friday 27th July 1962, a conversation was about to set in motion a chain of events that would lead to Pete Best leaving The Beatles and eventually being replaced by Ringo Starr.

The Beatles were playing on the same bill as Joe Brown and the Bruvvers at the Tower Ballroom, New Brighton, a show promoted by Bob Wooler. As featured in Finding the Fourth Beatle, Bobby Graham was the first drummer to be approached to replace Pete and, in the estimation of John, Paul and George, ideally suited for The Beatles and more than adequate for George Martin’s needs. After all, the producer’s problem with Pete had nothing to do with his live performances, but rather his drumming in the studio. Graham had extensive studio experience and, as would be proved, was one of the top session drummers in the ‘60s. Unfortunately for Brian, Graham turned him down.

As Graham recalled: “He said that they needed a change. I said, ‘No thanks’ as The Beatles hadn’t had any hits and anyway, I had a wife and family in London. I don’t think he had even discussed it with The Beatles, as surely they would have wanted someone from Liverpool.”

In a further interview with Spencer Leigh, Graham elaborated further on the discussion. “Brian Epstein invited us back to the Blue Angel after the show. He called me to one side and said he was having trouble with Pete Best’s mum and he wanted him out of The Beatles. He asked me if I would take his place. Although I liked The Beatles, I turned him down because I didn’t want to come to Liverpool. Besides, I liked Joe Brown, who was having hit records.”

It has been suggested that Bobby Graham wasn’t offered the permanent job. According to Mark Lewisohn in TuneIn: “He (Brian) can’t have been offering the position permanently – John, Paul and George were clear they wanted Ringo – but Ringo was at Butlin’s until early September…. Brian wondered if Graham could bridge the gap between Pete’s departure and Ringo’s return.” However, this is a speculation and there is no evidence to support this theory.

Bobby Graham was one of four drummers asked to replace Pete Best: Ringo was the one who accepted the job, and became The Fourth Beatle.

The full story is in Finding the Fourth Beatle. To purchase this, and David’s other books, go to www.beatlesbookstore.com

David Bedford

22nd February 1963 – Ask Me Why: Lennon and McCartney’s Publishing Contract

24th March 1963 – Bobby Graham: Almost a Beatle – Twice

18th June 1963 – Paul McCartney’s 21st birthday, and other coincidences